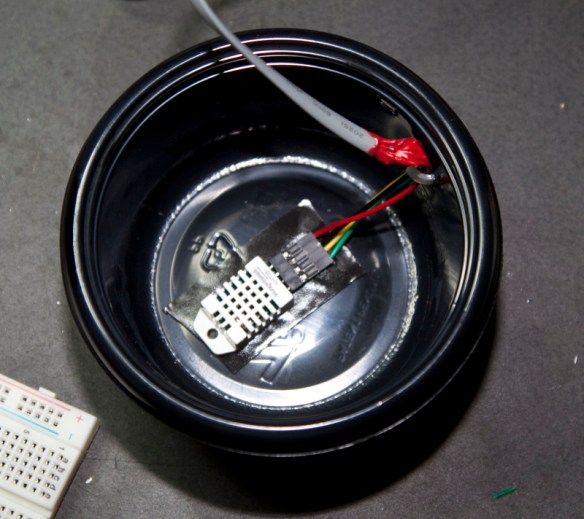

I installed the Sparkfun Weather Meters mainly for the rain gauge. It is quite expensive, and didn’t even come with the small screws which hold the anemometer and wind vane to the support arm. It does seem to be well made, and makes my system look like a weather station.

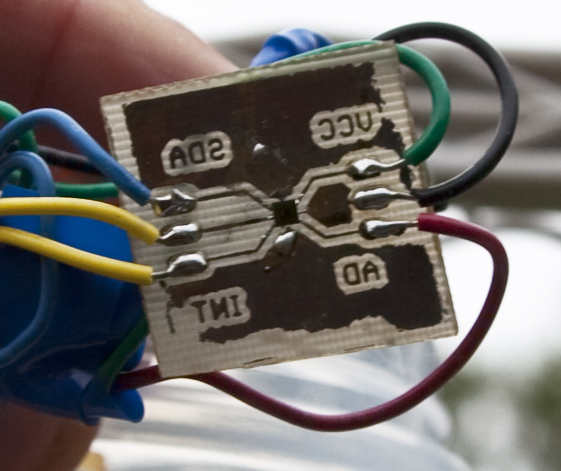

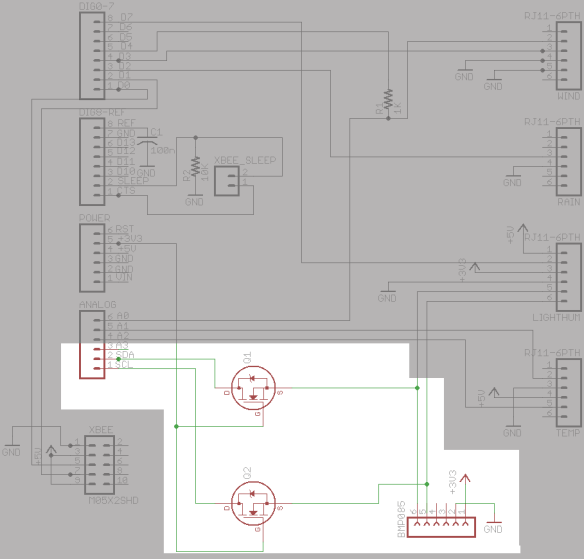

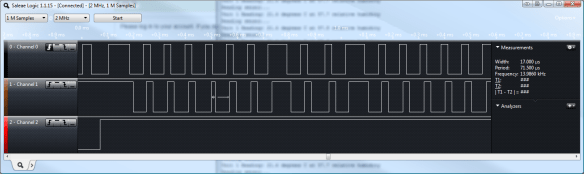

The datasheet shows that the rain gauge and the anemometer are magnetic reed switches; every 0.011″ of rain causes a momentary contact and a 2.4km/h wind will cause a momentary contact every second for the anemometer. These inputs will be connected to Arduino interrupts. The wind vane uses an array of resistors which can be read through the ADC of the Arduino, but the datasheet is wrong for the wind vane. At 315°, the datasheet states that the voltage should be 4.78V, but in actuality, with a 10K resistor in series with a 64.9K resistor, the voltage drop across the vane will be 4.33V.

The following code setups up the inputs and the interrupts to read this device. Note that setting a pin to INPUT and then writing a HIGH value to it turns on the internal 20K pull up resistor in the Arduino, which prevents the need for external pull up resistors on the interrupt driven devices. The wind vane requires a 10K resistor in series with the vane’s resistors, and to save power, this resistor and the vane are powered from a digital output, which is driven HIGH only when the reading is to be taken.

#define ANEMOMETER_PIN 3

#define ANEMOMETER_INT 1

#define VANE_PWR 4

#define VANE_PIN A0

#define RAIN_GAUGE_PIN 2

#define RAIN_GAUGE_INT 0

void setupWeatherInts()

{

pinMode(ANEMOMETER_PIN,INPUT);

digitalWrite(ANEMOMETER_PIN,HIGH); // Turn on the internal Pull Up Resistor

pinMode(RAIN_GAUGE_PIN,INPUT);

digitalWrite(RAIN_GAUGE_PIN,HIGH); // Turn on the internal Pull Up Resistor

pinMode(VANE_PWR,OUTPUT);

digitalWrite(VANE_PWR,LOW);

attachInterrupt(ANEMOMETER_INT,anemometerClick,FALLING);

attachInterrupt(RAIN_GAUGE_INT,rainGageClick,FALLING);

interrupts();

}

In order for the anemometer to be accurate, any surrounding objects must be 4 time as far as they are higher than the anemometer. For example, if my anemometer is 5 feet off the ground, and my house is 25 feet tall, the anemometer would need to be 80 feet from the house to be able to measure the wind speed accurately. In my case, nothing close to this leeway is possible, but I still setup the anemometer just for the educational experience.

Every rotation of the anemometer causes a call to the interrupt service routine anemometerClick(). Switch debouncing is accomplished by assuming any interrupt that occurs within 500 uS of the previous one is a bounce and should be ignored. This limits the max speed this configuration can measure to about 2900 miles per hour, but since I don’t live on Jupiter I think I can live with this compromise. The getUnitWind() function returns the average wind speed since the last poll, which is every 60 seconds. The getGust function uses the shortest time between 2 interrupts to calculate the fastest wind speed since the last poll.

#define WIND_FACTOR 2.4

#define TEST_PAUSE 60000

volatile unsigned long anem_count=0;

volatile unsigned long anem_last=0;

volatile unsigned long anem_min=0xffffffff;

double getUnitWind()

{

unsigned long reading=anem_count;

anem_count=0;

return (WIND_FACTOR*reading)/(TEST_PAUSE/1000);

}

double getGust()

{

unsigned long reading=anem_min;

anem_min=0xffffffff;

double time=reading/1000000.0;

return (1/(reading/1000000.0))*WIND_FACTOR;

}

void anemometerClick()

{

long thisTime=micros()-anem_last;

anem_last=micros();

if(thisTime>500)

{

anem_count++;

if(thisTime<anem_min)

{

anem_min=thisTime;

}

}

}

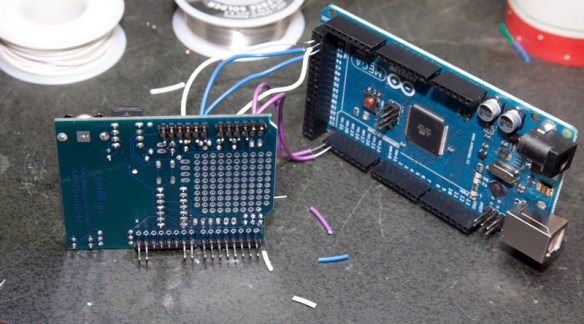

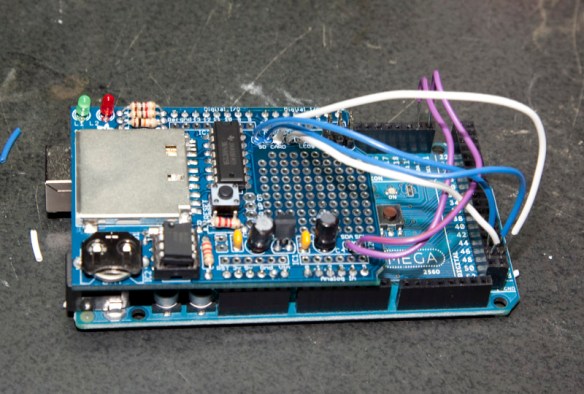

When the system included the logger shield, SRAM memory was so tight that I had to move variable data from SRAM to FLASH. Using PROGMEM allowed me to move the vane directions and the expected values out of SRAM, and in itself saved almost 100 bytes of the 2000 the Arduino has (moving String values in addition freed up about 500 bytes of SRAM). The pgm_read_word function pulls the values out of FLASH and into SRAM when needed, but only works with integers, so the actual wind directions are stored as 10X their value.

As mentioned in the MCP9700 post, the analogReference for the Wind Vane must be switched from the 1.1V the MCP9700 was using to the 5V default value. Since it takes some time for the ADC to adjust to the new reference, the first 10 adc readings are just thrown out.

To save battery power, the wind vane is powered by the digital pin VANE_PWR right before it is used. a 100ms delay is inserted after the power pin is driven high just to left things settle down. The rest of the function compares the ADC value to the ideal values in vaneValues, and returns the corresponding wind direction.

static int vaneValues[] PROGMEM={66,84,92,127,184,244,287,406,461,600,631,702,786,827,889,946};

static int vaneDirections[] PROGMEM={1125,675,900,1575,1350,2025,1800,225,450,2475,2250,3375,0,2925,3150,2700};

double getWindVane()

{

analogReference(DEFAULT);

digitalWrite(VANE_PWR,HIGH);

delay(100);

for(int n=0;n<10;n++)

{

analogRead(VANE_PIN);

}

unsigned int reading=analogRead(VANE_PIN);

digitalWrite(VANE_PWR,LOW);

unsigned int lastDiff=2048;

for (int n=0;n<16;n++)

{

int diff=reading-pgm_read_word(&vaneValues[n]);

diff=abs(diff);

if(diff==0)

return pgm_read_word(&vaneDirections[n])/10.0;

if(diff>lastDiff)

{

return pgm_read_word(&vaneDirections[n-1])/10.0;

}

lastDiff=diff;

}

return pgm_read_word(&vaneDirections[15])/10.0;

}

The rain gauge work much like the anemometer in that it drives an interrupt, and a 500us debounce time is used. The interrupt the simply counts the number of switch contacts that occurred since the last poll and multiplies that by the number of mm of rain each switch contact represents.

#define RAIN_FACTOR 0.2794

volatile unsigned long rain_count=0;

volatile unsigned long rain_last=0;

double getUnitRain()

{

unsigned long reading=rain_count;

rain_count=0;

double unit_rain=reading*RAIN_FACTOR;

return unit_rain;

}

void rainGageClick()

{

long thisTime=micros()-rain_last;

rain_last=micros();

if(thisTime>500)

{

rain_count++;

}

}